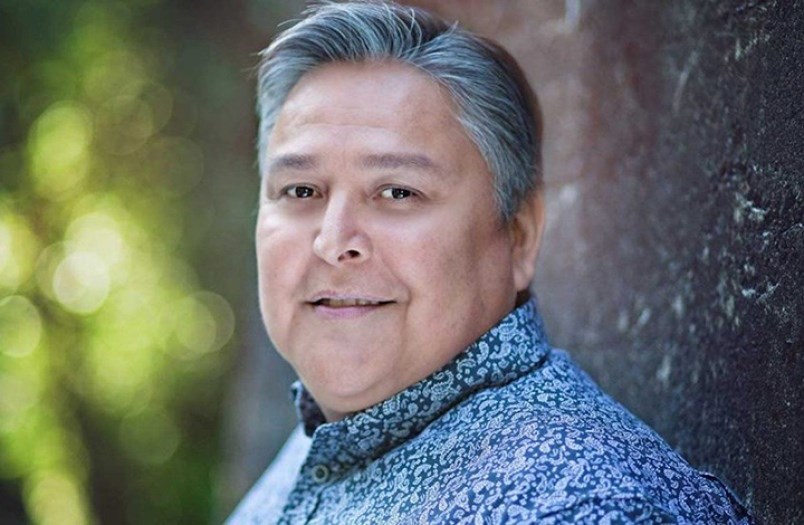

Last week in a virtual Q&A session, Indigenous author Bob Joseph was asked “How will people know that they’ve achieved reconciliation?”

Joseph answered, “When people are at peace with the past.”

The first step is moving away from the Indian Act, according to Joseph, who advocates for First Nations heading toward self-governance, self-reliance and self-determination.

The bestselling author of ‘21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act’ has been enabling discourse about the act since his 2015 blog post about the legislation went viral. In Canada, many people are still oblivious to the Indian Act, says Joseph.

Since it was first passed in 1876, the Indian Act has undergone numerous amendments but it still stands as law, governing matters pertaining to Indian status, bands and reserves, among other things.

The legislation – originally created to ‘assimilate’ Indigenous people into mainstream Canadian life and values – is a paradox in which both the rights of Indigenous people and their bondage co-exist.

And while some Indigenous groups have called for its dismissal due to what has been called its regressive and paternalistic excesses, others have resisted its abolition.

Joseph is a member of the Gwawa’enuxw Nation, Gayaxala (Thunderbird) clan, who grew up in Campbell River. He believes the Indian Act must go, simply because it was unsuccessful (and now outdated) in its original purpose of assimilating Indigenous people into the political and economic mainstream.

“If anything, it (the Indian Act) has kept Indigenous people separate under different laws and under different lands,” he says.

In a virtual seminar last week hosted by the Vancouver Island Regional Library, Joseph interacted with more than 500 viewers. He provided insights into the legislation’s history before discussing modern-day solutions that could replace the Indian Act.

Through 21 points Joseph not only highlighted the obsolete nature of the legislation but also why it is relevant to understanding reconciliation going forward – especially at a time when Canada is undertaking a commitment to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Before some of its amendments, the Indian Act denied Indigenous status to women, introduced residential schools, created reserves, renamed individuals with European names, restricted First Nations from leaving reserves without permission from Indian Agents, expropriated portions of reserves for roads, railways, etc, imposed the ‘band council’ system and created other personal and cultural tragedies on First Nations.

Despite that, it was legally significant for Indigenous peoples. For example, in 1969 when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s white paper policies proposed to abolish it, Aboriginal leaders across Canada opposed the move. Since the Indian Act affirms the historical and constitutional relationship Aboriginal peoples have with Canada, they wanted it to legally maintain the Indian status and the rights that it afforded them.

This paradox, Joseph pointed out, has created a relationship wherein Indigenous people are dependent on the federal government. Even today, these concerns remain when discussions about breaking away from the Indian Act comes up.

“I hear people tell me, ‘We need to make sure we protect our status.’” He reminds them that thought is “in fact an objective of the Indian Act” which keeps them tied to it. The Indian act will never help them grow their nation and their people – “it’s not designed to do that.” That is why First Nations must find a better way, break the cycle of dependency and give way to self-determination, self-reliance, and self-governance.

“A place to look for solutions already exists,” he says, pointing to modern-day treaties in B.C. like the Nisga’a Treaty and the Westbank First Nation Self-government Agreement from the early 2000s.

“The Nisga’a Treaty got rid of the Indian Act, they were able to get control and jurisdiction over lands and resources and the ability to make decisions about those lands and resources.”

But he also says that these treaties are not necessarily a one-size-fits-all framework that will work for all Nations. Each group must arrive at a model that works best for them through negotiations.

This is where knowledge of history comes in handy – for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people – as a powerful medium to achieve true reconciliation.

As people become aware of the history of Indigenous people in Canada through the ages, there is a wider scope of conversation that can be had in families, educational institutions, places of worship, etc.

He urges people to learn about history and then make a personal pledge to reconciliation – which is going to take “political will, knowledge and understanding and empathy.”

“Reconciliation has to be a grassroots movement and not by politicians,” he says.

Because when it comes to something as important as reconciliation, politics “holds back” the process of moving away from the Indian Act as “politicians are all over the place,” with government agendas changing every four years.

“I would rather hang my hat on individuals in Canada to do reconciliation. That seems to have a lot more longevity.”

When political agendas come into the picture, conversations pivot to the “cost of change,” that First Nations are asking for.

To drive home the point, Joseph gives an example from the early ’90s when he had a conversation with a group of people who were worried after a front-page article in the Vancouver Sun stating Indian land claims could cost taxpayers $10 billion.

“I told them this was a great article. It talks to you about the cost of change, but it doesn’t talk to you about the cost of not changing it,” he says, adding, cost of years-long legal battles, loss of direct investments and jobs, etc, ultimately end up costing governments more than the estimated cost of change.

“So I try to tell taxpayers, look, if it’s money you’re worried about, if that’s what makes your world go round. I can tell you honestly, it will be cheaper to resolve land claims quicker than it is to let them fester.”

Such issues resurface at different intervals of history, he warns, referring to the ongoing Wet’suwet’an pipeline conflict in B.C. and it’s all because there’s no relationship with Indigenous people.

“We’re not listening to their concerns.”

Which is why in retrospect, Joseph says it would be cheaper to move away from the Indian Act and have mutually beneficial relationships.

“It will be better for the country.”