NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) ŌĆö In 1989, Americans were riveted by the in their Beverly Hills mansion by their own children. Lyle and Erik Menendez were sentenced to life in prison and lost all subsequent appeals. But today, more than three decades later, they unexpectedly have a chance of getting out.

Not because of the workings of the legal system. Because of entertainment.

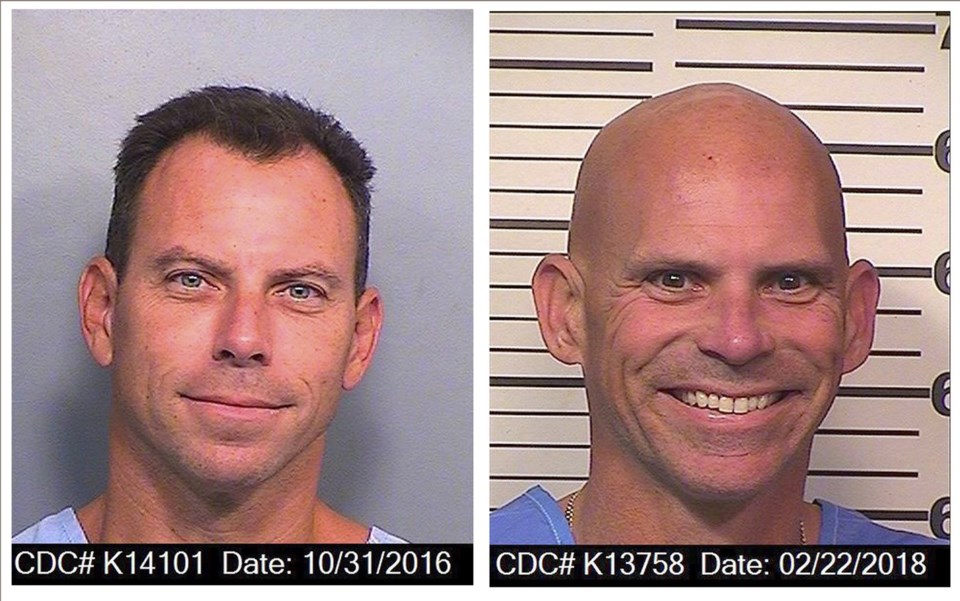

After two recent documentaries and a scripted drama on the pair brought new attention to the 35-year-old case, the Los Angeles they be resentenced.

The popularity and proliferation of true crime entertainment like NetflixŌĆÖs docudrama is effecting real life changes for their subjects and in society more broadly. At their best, true crime podcasts, streaming series and social media content can help expose injustices and right wrongs.

But because many of these products prioritize entertainment and profit, they also can have serious negative consequences.

It may help the Menendez brothers

The use of true crime stories to sell a product has a long history in America, from the tabloid ŌĆ£penny pressŌĆØ papers of the mid-1800s to television movies like 1984's ŌĆ£The Burning Bed." These days it's podcasts, bingeable Netflix series and even true crime TikToks. The fascination with the genre may be considered morbid by some, but it can be partially explained by the human desire to make sense of the world through stories.

In the case of the Menendez brothers, , who was then 21, and Erik, then 18, have said they feared their parents were about to kill them to prevent the disclosure of the fatherŌĆÖs long-term sexual molestation of Erik. But at their trial, many of the sex abuse allegations were not allowed to be presented to the jury, and prosecutors contended they committed murder simply to get at their parentsŌĆÖ money.

For years, that's the story that many people who watched the saga from a distance accepted and talked about.

The new dramas delve into the brothers' childhood, helping the public better understand the context of the crime and thus see the world as a less frightening place, says Adam Banner, a criminal defense attorney who writes a column on pop culture and the law for the American Bar AssociationŌĆÖs ABA Journal.

ŌĆ£Not only does that make us feel better intrinsically," Banner says, ŌĆ£but it also objectively gives us the ability to think, ŌĆśWell, now I can take this case and put it in a different bucket than another situation where I have no explanation and the only thing I can say is, ŌĆśThis child just must be evil.'ŌĆØ

The rise of the antihero is at play

Much true crime of the past takes particularly shocking crimes and explores them in depth, generally with the assumption that those convicted of the crime were actually guilty and deserved to be punished.

The success of the podcast ŌĆ£ ,ŌĆØ which cast doubt on the , has given birth to a newer genre that often assumes (and intends to prove) the opposite. The protagonists are innocent, or ŌĆö as in the case of the Menendez brothers ŌĆö guilty but sympathetic, and thus not deserving of their harsh sentences.

ŌĆ£There is an old tradition of journalists picking apart criminal cases and showing that people are potentially innocent,ŌĆØ says Maurice Chammah, a staff writer at The Marshall Project and author of ŌĆ£Let the Lord Sort Them: The Rise and Fall of the Death Penalty."

ŌĆ£But I think that the curve kind of goes up exponentially in the wake of ŌĆśSerial,ŌĆÖ which was 2014 and obviously changed the entire landscape economically and culturally of podcasts," Chammah says. "And then you have ŌĆśMaking a MurdererŌĆÖ come along a few years later and become a kind of behemoth example of that in docuseries.ŌĆØ

Roughly during the same time period, the innocence movement gained traction along with the Black Lives Matter movement and greater attention on police custody deaths. And in popular culture, both fiction and nonfiction, the trend is to mine a villainous character's backstory.

ŌĆ£All these superheroes, supervillains, the movie ŌĆśJoker' ŌĆö youŌĆÖre just inundated with this idea that peopleŌĆÖs bad behavior is shaped by trauma when they were younger,ŌĆØ Chammah said.

Banner often represents some of the least sympathetic defendants imaginable, including those accused of child sexual abuse. He says the effects of these cultural trends are real. Juries today are more likely to give his clients the benefit of the doubt and are more skeptical of police and prosecutors. But he also worries about the intense focus in current true crime on cases where things went wrong, which he says are the outliers.

While the puzzle aspect of ŌĆ£Did they get it right?ŌĆØ might feed our curiosity, he says, we run the risk of sowing distrust in the entire criminal justice system.

ŌĆ£You donŌĆÖt want to take away the positive ramifications that putting that spotlight on a case can bring. But you also donŌĆÖt want to give off the impression that this is how our justice system works. That if we can get enough cameras and microphones on a case, then thatŌĆÖs how weŌĆÖre going to save somebody off of death row or thatŌĆÖs how weŌĆÖre going to get a life sentence overturned.ŌĆØ

Adds Chammah: "If you open up sentencing decisions and second looks and criminal justice policy to pop culture ŌĆö in the sense of who gets a podcast made about them, who gets Kim Kardashian talking about them ŌĆö the risk of extreme arbitrariness is really great. ... It feels like itŌĆÖs only a matter of time before the wealthy family of some defendant basically funds a podcast that tries to make a viral case for their innocence.ŌĆØ

The audience is a factor, too

Whitney Phillips, who teaches a class on true crime and media ethics at the University of Oregon, says the popularity of the genre on social media adds another layer of complications, often encouraging active participation of viewer and listeners.

ŌĆ£Because these are not trained detectives or people who have any actual subject area expertise in forensics or even criminal law, then thereŌĆÖs this really common outcome of the wrong people being implicated or floated as suspects," she says. "Also, the victims' families now are part of the discourse. They might be accused of this, that, or the other, or at the very least, you have your loved one's murder, violent death, being entertainment for millions of strangers.ŌĆØ

This sensibility has been both chronicled and lampooned in the streaming comedy-drama series which follows three unlikely collaborators who live in a New York apartment building where a murder has taken place. The trio decide to make a true crime podcast while simultaneously trying to solve the case.

Nothing about true crime is fundamentally unethical, Phillips says. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs that the social media system ŌĆö the attention economy ŌĆö is not calibrated for ethics. ItŌĆÖs calibrated for views, itŌĆÖs calibrated for engagement and itŌĆÖs calibrated for sensationalism."

Many influencers are now vying for the ŌĆ£murder audience,ŌĆØ Phillips says, with social media and more traditional media feeding off each other. True crime is now creeping into lifestyle content and even makeup tutorials.

ŌĆ£It was sort of inevitable that you would see the collision of these two things and having these influencers literally just put on a face of makeup and then tell a very kind of ŌĆö itŌĆÖs very informal, itŌĆÖs very dishy, itŌĆÖs often not particularly well researched," she says. ŌĆ£This is not investigative journalism.ŌĆØ

Travis Loller, The Associated Press