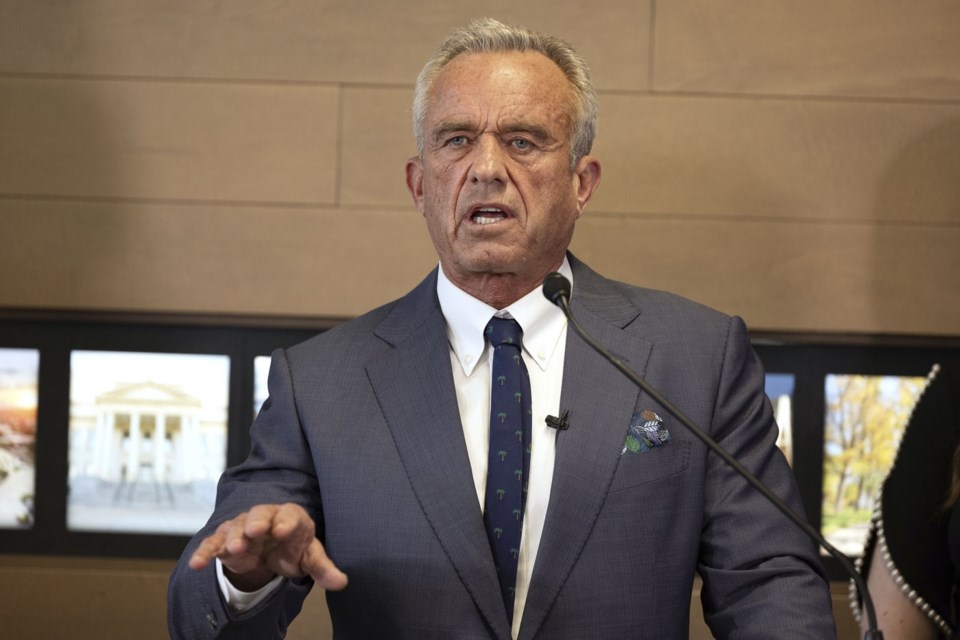

NEW YORK (AP) — U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has said he wants communities , and he is setting the gears of government in motion to help make that happen.

Kennedy this week said he plans to tell the to stop recommending fluoridation in communities nationwide. And he said he’s assembling a task force of health experts to study the issue and make new recommendations.

At the same time, the announced it would review new scientific information on potential health risks of fluoride in drinking water. The EPA sets the maximum level allowed in public water systems.

Here's a look at how reversing fluoride policy has become an action item under President Donald Trump's administration.

The benefits of fluoride

Fluoride strengthens teeth and reduces cavities by , according to the CDC. In 1950, federal officials endorsed water fluoridation to prevent tooth decay, and in 1962 set guidelines for how much should be added to water.

Fluoride can come from a number of sources, but drinking water is the main one for Americans, researchers say. Nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population gets , according to CDC data.

The addition of low levels of fluoride to drinking water was long considered one of the greatest public health achievements of the last century. The American Dental Association credits it with reducing tooth decay by more than 25% in children and adults.

About one-third of community water systems — 17,000 out of 51,000 across the U.S. — serving more than 60% of the population fluoridated their water, according to a 2022 CDC analysis.

The potential problems of too much fluoride

The CDC currently recommends 0.7 milligrams of fluoride per liter of water.

Over time, studies have documented potential problems when people get much more than that.

Excess fluoride intake has been associated with streaking or spots on teeth. And studies also have traced a link between excess fluoride and brain development.

A last year by the federal government’s National Toxicology Program, which summarized studies conducted in Canada, China, India, Iran, Pakistan and Mexico, concluded that drinking water with more than 1.5 milligrams of fluoride per liter — more than twice the CDC's recommended level — was associated with lower IQs in kids.

Meanwhile, last year, a federal judge to further regulate fluoride in drinking water. U.S. District Judge Edward Chen cautioned that it’s not certain fluoride is causing lower IQ in kids, but he concluded that research pointed to an unreasonable risk that it could be.

Kennedy has railed against fluoride

Kennedy, a former environmental lawyer, has fluoride a “dangerous neurotoxin” and “an industrial waste” tied to a range of health dangers. He has said it’s been associated with arthritis, bone breaks, and thyroid disease.

Some studies have suggested such links might exist, usually at higher-than-recommended fluoride levels, though some reviewers have questioned the quality of available evidence and said no definitive conclusions can be drawn.

How fluoride recommendations can be changed

The CDC's recommendations are widely followed but not mandatory.

State and local governments decide whether to add fluoride to water and, if so, how much — as long as it doesn’t exceed the EPA's limit of 4 milligrams per liter.

So Kennedy can’t order communities to stop fluoridation, but he can tell the CDC to stop recommending it.

It would be customary to convene a panel of experts to comb through the research and assess the evidence that speak to the pros and cons of water fluoridation. But Kennedy has the power to stop or change a CDC recommendation without that.

“The power lies with the secretary,” but public trust would erode if recommendations are changed without a clear scientific basis, said Lawrence Gostin, a public health law expert at Georgetown University.

“If you’re really serious about this, you don’t just come in and change it,” he said. “You ask somebody like the National Academy of Sciences to do a study — and then you follow their recommendations.”

On Monday, Kennedy said he was forming a task force to focus on fluoride, while at the same time saying he would order the CDC to stop recommending it.

HHS officials did not answer immediately questions seeking more information about what the task force would be doing.

Some places are already pulling back on fluoridation

Utah recently became in drinking water, and legislators elsewhere are looking at the issue.

An Associated Press analysis of CDC data for 36 states shows that many communities in recent years.

Over the last six years, at least 734 water systems that consistently reported their data in those states have stopped fluoridating water, according to the AP's analysis.

Mississippi alone accounted for more than 1 in 5 of those water systems that stopped. Most water systems that discontinued fluoridation mainly did so to save money, said Melissa Parker, the Mississippi state health department’s assistant senior deputy.

During the pandemic, Mississippi’s health department allowed local water systems to temporarily cease fluoridating because they could not purchase sodium fluoride in the midst of global supply chain issues. Many never restarted, Parker said.

CDC funding for fluoride is typically a small factor

Since 2003, CDC has funded a limited number of state oral health programs through cooperative agreements. The agreements run in cycles, and at the beginning of this year 15 states were each receiving $380,000 over three years.

The money can be used on a number of things, including collecting data on people with dental problems, dental care and technical assistance for community water fluoridation activities.

The current oral health funding is going to Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Nevada, New York, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia and Wisconsin.

The states are told not to use the money for chemicals, because the funding is intended to help set up fluoridation, not for everyday expenses, federal officials have said. South Carolina, for example, sets aside up to $50,000 to help communities in that state fluoridate. Iowa spends about $65,000 to promote community water fluoridation.

Earlier this year, CDC officials declined to answer questions about how much of the total oral health money has been going toward fluoridation.

Now, there is no one to ask: Last week, the CDC’s entire 20-person Division of Oral Health was eliminated as part of .

Congress appropriated money to CDC specifically to support oral health programs, and some congressional staffers say the agency must distribute those funds no matter who is running the HHS or CDC. But have struck at a number of programs that Congress had called for, and it's not clear what will happen to the CDC oral health funding.

Fluoridation is relatively cheap compared with other water department expenses, and most communities simply incorporate the cost into the water rates charged to customers, according to the American Water Works Association.

In Erie, Pennsylvania, for example, fluoridating water for 220,000 people costs about $35,000 to $45,000 a year and is entirely funded by water rates, said Craig Palmer, the chief executive of the Erie Water Authority.

So cutting off the CDC money would not have much impact on most communities, some experts said, although it could be more impactful for some smaller, rural communities.

___

Pananjady reported from Philadelphia.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Mike Stobbe And Kasturi Pananjady, The Associated Press