The B.C. government-run corporation responsible for auctioning off 20 per cent of the province’s annual allowable cut gave a green light to companies looking to log certain old-growth forests slated for deferral, documents show.

In a BC Timber Sales (BCTS) memorandum dated May 15, 2023, BCTS told industry that in cases where First Nations said they needed more time or hadn’t responded to proposed old-growth deferrals, “Ancient” and “Priority Big-treed” forests should be deemed “available for harvest.”

The guidance memo also tells logging companies they can build roads through old-growth areas identified for deferral if there is no alternative route available that is “practical and reasonably economically feasible.”

“That scares me,” said Spô’zêm First Nation chief James Hobart after reviewing the memo. “Our expectation is that they were not going to log as the talks were going on.”

“It kind of puts us over a barrel.”

'A lot of talk and continued logging'

The details of the guidance document, first reported on by Glacier Media, have prompted a number of critics to slam the B.C. government for backtracking on public commitments to overhaul forestry policy.

Three years ago this week, the released 14 recommendations that together would represent a “paradigm shift” in the way B.C.’s forests are managed — from one focused on extraction to a model that prioritizes ecosystem health.

But to date, none of those recommendations have been enacted on the ground, said several environmental groups and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs in a joint Monday.

“We were pretty hopeful in 2020. This was seen as vindication. It was essentially what we had been asking for all along,” said Torrance Coste, national campaign director for the Wilderness Committee.

“What we’ve seen since is a lot of talk and continued logging.”

Run out of the Ministry of Forests, BC Timber Sales manages and auctions off about a fifth of B.C.'s forests approved for cutting every year, making it the largest forest tenure holder in the province.

A spokesperson for the ministry said BCTS “respects the recommendations of the Old Growth Strategic Review” and its operations are consistent with government plans around old-growth deferrals.

The latest memo, meanwhile, refers to a “very small number of instances” in which First Nations need more time or haven't responded to the proposed deferrals, said the spokesperson.

“Currently, there are nine First Nations that either haven’t responded or have said they need more time,” said the spokesperson in an email. “This represents a very small area and does not result in any net decrease in deferred old growth.”

The ministry added that harvest of ancient or big treed areas “must still go through consultation.”

Big-treed harvest approval most concerning, says ecologist who made government maps

Rachel Holt, an independent forest ecologist who served as a member of B.C.’s old-growth technical advisory panel, helped identify three categories of old growth that together are integral in protecting B.C.’s oldest forests.

Holt said the passages of the memo that approve the harvest of big-treed old growth are among the most concerning.

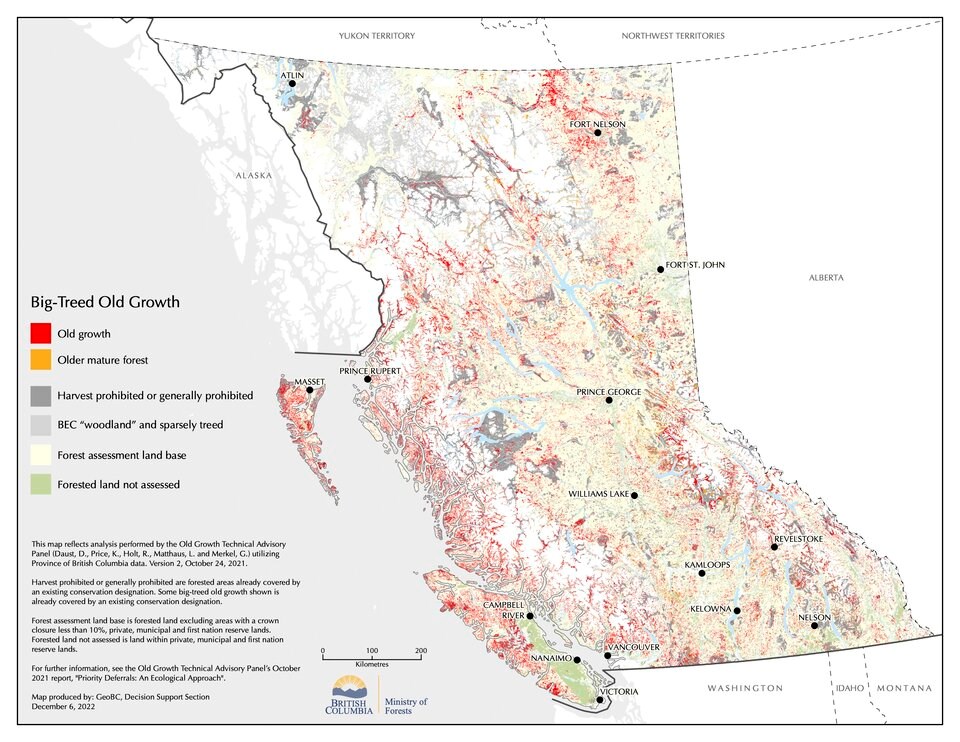

“Big-treed old growth” is considered “naturally rare” compared to its historic distribution, according to the Technical Advisory Panel's agreed-upon definition. It has been heavily targeted in the past and is currently facing “extremely high near-term risk.”

“They are the ones that have seen the most harvesting, so they are the ones that are most at risk now and most need that deferral,” Holt said. “That is really problematic that they are not acknowledging that.”

An “ancient forest,” which the latest memo says can be harvested in some cases, is considered globally rare and are considered particularly irreplaceable because of the time they take to grow back. Trees can range from more than 400 years old in places on the coast to 200-plus years old where ecosystems are naturally disturbed by things like wildfire.

The third category of old growth, “remnant old ecosystems,” are considered rare, and occur in places where forests have experienced heavy harvesting, leaving very little old growth left.

Two years after Holt and her colleagues produced the latest proposed , she says the province remains at a crossroads in a push to protect the last remaining old growth.

“And this kind of memo I find concerning,” Holt said. “It suggests [the B.C. government is] leaning towards tweaking around the edges, rather than the full paradigm shift.”

'Full steam ahead'

Eddie Petryshen, a conservation specialist with the Kootenay-based group Wildsight, said that in the months after it was written, the document had been quietly passed among some environmental groups and scientists after people inside BCTS and industry leaked its existence.

“I was shocked when I first read it,” said Petryshen. “It totally doesn't comply with the public statements that have been made.”

When Wildsight and other environmental groups questioned the B.C. government over the memo, it was . The names of those who wrote or approved the document had been removed.

The May 2023 memo overrides past guidance, spelling out what to do under three scenarios.

In cases where a First Nation says it does not support old-growth deferrals or it has yet to answer the government, BCTS says companies can log ancient and/or priority old-growth forests. Remnant old ecosystems remain off limits.

When a First Nation says they do support proposed old-growth deferrals, logging companies are directed to field check if the old forests meet the criteria for big treed, ancient forests or remnant old ecosystems. If they don’t meet the criteria, “proceed with development,” says the BCTS memo.

In another section, the memo also says logging companies can build roads through old-growth areas identified for deferral if there is no alternative route available that is “practical and reasonably economically feasible.”

A spokesperson with the Ministry of Forests said “BCTS engages with all First Nations in whose territory their activities intersect” — whether that is on cut blocks or in the building of forest service roads.

But critics remain skeptical of the new guidance. Petryshen said the B.C. government’s move to defer old-growth logging was a first step in taking responsibility for the state of many B.C. forests, and a commitment to consult First Nations under the principals of “free, prior and informed consent.”

“And this is backtracking on that,” Petryshen said of the latest memo. “It's a big shift.”

“It’s full steam ahead.”

Chief says it's time to disband BCTS, create Indigenous forestry management board

Hobart says that fallout from the memo could be hugely problematic, and not just for First Nations like the Spô’zêm, who have backed old-growth deferrals in their territory and is leading local efforts to protect the habitat of the last wild-born northern spotted owl in Canada.

Many First Nations need time to bring the proposals forward to a long list of community members, including Elders and knowledge-keepers, Hobart said. If in the end they decide to support the old-growth deferrals, nations then need to figure out how to both pay their short-term bills and advance their long-term economic development, he said.

“We’re saying, ‘You don’t need to go logging. You need the money.’ That’s what it’s about in the end,” said the Chief, pointing to an opportunity in ecotourism businesses.

The latest BCTS memo couldn't have come at a worse time, said Hobart, pointing to government commitments to truth and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, the twin pressures of climate change and species extinction, and the fact that 2023 has emerged as B.C.'s worst wildfire season on record.

Considering the government's commitments to rebuild and protect forest habitats, Hobart said it provides one more example of why the corporation should be disbanded and its funding be transferred to First Nations to create their own forestry management board.

“BC Timber Sales has the worst record of consulting with First Nations,” Hobart said. “They’ve mismanaged grossly.”

“They’ve already taken it past a place of no return.”