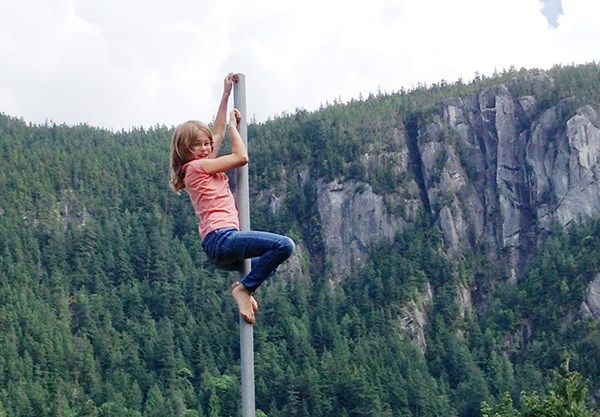

Let’s delve a little deeper – or go a little higher – into the complex lexicon that makes up climbing language. Hopefully they will help inform the greater �鶹�����population on some of the different ideas and styles within the activity of climbing.

Save these definitions, put them up on your fridge and memorize them. They’re sure to come in handy one day while you need to impress someone while standing in line for the gondola, having a pint at a local pub or chatting with your rebellious teenager.

Belay: Belaying, as a verb, is when the partner to the climber holds the other end of her rope and stops a fall before the climber hits the ground. This happens by applying friction through different types of metal gear or, at its simplest, around one’s body. This job is surprisingly simple but has dire consequences if done incorrectly. This is where the partnership aspect in climbing becomes obvious; it is not a solitary sport.

Top rope climbing: This form of climbing is actually a tool to help introduce the novice to basic climbing movement, anchor building basics and belay skills. Similar to a climbing gym, the rope is anchored through points at the top, the climber ties into one end and the belayer minds the slack end. As the climber ascends the belayer takes in her extra slack and, when done, he lowers her to the ground. Done properly, top roping virtually eliminates much of the risk in climbing, barring the cliff falling down or a jet crashing into the cliff while you are climbing there.

Lead climbing: The progression from top rope climbing in which you now climb the cliff, dragging your rope up from the base as you go, instead of building an anchor at the top and putting your rope through it. Now you risk real falls, have to recognize real hazards as you ascend and the belayer has a much more intense job. Lead climbing is where you actually walk up, climb the cliff, protect yourself accordingly, descend, pull your rope and walk away a hero.

Traditional climbing: As the name implies, this form was created ages ago when people’s ethics were pure. It grew out of a common goal to improve upon the damaging style of aid climbing. You climb the rock using your bodily skills for upwards progress and relying on temporary, removable protection placed into the rock along with your rope and belayer to stop a fall. Once climbed there is no protection left in the climb, leaving people to often refer to this as clean climbing. Squamish, with its beautiful array of vertical granite cracks, is a world renowned destination for this style of climbing.

Sport climbing: A style of free climbing and an outgrowth from traditional climbing in which risk is controlled by added permanent protection bolts which are drilled right into the rock. The rope is clipped to these and a belayer is used in the same way as all other free climbing forms. With bolts added into the stone, a climber doesn’t have to stay close to the cracks that accept the removable gear of traditional climbing. Sport climbing traded the clean climbing ethic for the ability to venture out onto the steeper, blanker sections of cliffs that were originally the domain of aid climbers. Gymnastic difficulty is the main pursuit in sport climbing and the most difficult routes in the world are climbs protected by bolts.

Bouldering: This is another offshoot of free climbing. Here we rid ourselves of the rope, the gear, the belayer and the cliff itself. Instead, a boulderer climbs on boulders pursuing absolute physical difficulty. Mind-bendingly creative techniques are employed to solve physical puzzles, and a fall means little more than hitting your bouldering pad. This is the fastest growing form of climbing because it’s relatively simple, cheap and can be used simply as a form of working out.

However, anyone who boulders outside knows there can be much more to it than simply a workout. You can go alone for soul-searching, meet up with friends for the social camaraderie, blast through the forest amassing many boulder problems or work on a single move until perfection for months, if not years.