This week’s column is a little departure from the big questions banging around within the topic of climbing, and instead focuses on my own climbing and the idea of community spirit gone awry.

For the past month the weather has been unbelievable, unprecedented and motivating if you’re a rock climber. This is definitely one of the reasons �鶹�����is the best climbing area in Canada; mild temperatures, fast-drying rock and a huge variety in styles of climbing from which to choose. My own climbing has swung more towards bouldering because of the birth of my daughter and because I can improve on my bouldering techniques. I needed a more convenient and time-efficient style of climbing to pursue but still needed to perpetually strive toward – or, more aptly, flog myself against – motivational goals. My training has evolved as well, with more reading, research and discussion with my fellow climbers and friends on how to make better use of our limited time to improve our strength, power, conditioning, injury prevention and focus.

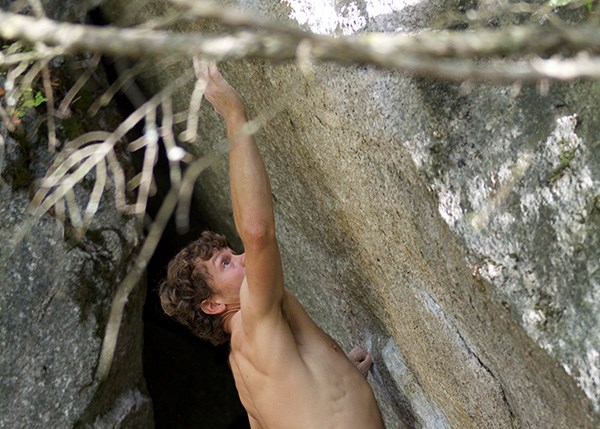

One of bouldering’s most interesting challenges is the idea of the project. Basically, it’s finding boulder problems that are at your physical limit and learning them, training for them and eventually doing them, all in the name of self-improvement. While it’s not the only thing you can learn through bouldering, the problem-solving and physical puzzling of the process, combined with the confidence required to stay focused on the prize, transfer well to other aspects of climbing as well as to life itself. I’m currently millimeters from success on a project but am coming up short, literally, because I’m not latching the lip of the boulder as I leap. My body swings out and away from the face as I jump and my centre of mass rips my right hand from the hold. This has happened too many times and despite going at night, using lights and squeezing in every available scrap of time I could, I’m out of chances to go back before going away Wednesday for a spring break getaway to the boulder fields of Bishop, California. This is truly a First World problem.

I used this roundabout path, educating you about �鶹�����bouldering and adding my own experience into the mix, to bring up the crux of this week’s column. In climbing, the most difficult section of a climb, whether a route or boulder problem, is referred to as its crux. This boulder problem I’ve been trying requires quite a few crash pads to protect the boulderer from a rocky and uneven landing. Added to this is the crucial need for a spotter so that I don’t miss the final move, swing off and go torpedoing upside down into the boulder behind and then into the deep Salal and Alder behind that. Enough pads are needed that I had stashed one of my own in a cave beneath the boulder so I didn’t need to bring so many each trip. This pad stashing is very common in the Grand Wall Boulders and if you know where to look, you’ll find a host of older, soft, slightly mildewed pads.

The other day, my last chance to try my project, I arrived at the boulder to find the ripped, old, brown Metolius pad, which I had stashed, gone. Someone had re-appropriated it. I didn’t go home and cry, nor did I curse to the heavens using foul language. I was, however, bummed out that in a community as close and likeminded as the climbing community, someone would take a stashed pad and not replace it once done. They’re free for the using but need to be returned. This is a community shout out to whoever moved my Ol’Brown, please put it back where you found it near Gibbs Cave, at the Defenders Boulder.

Perhaps someone thought it was just garbage? I assure you that stashed pads rarely become permanent garbage in there because without exception, the people who climb in those woods treat it as a very special place. Come home, Old Brown!