Editor's note: Please be aware that some information detailed in this story about residential school survival is difficult to hear and may be triggering for some readers. Please take good care and contact toll-free 1 (800) 721-0066 or 24hr Crisis Line 1 (866) 925-4419 if support is needed.

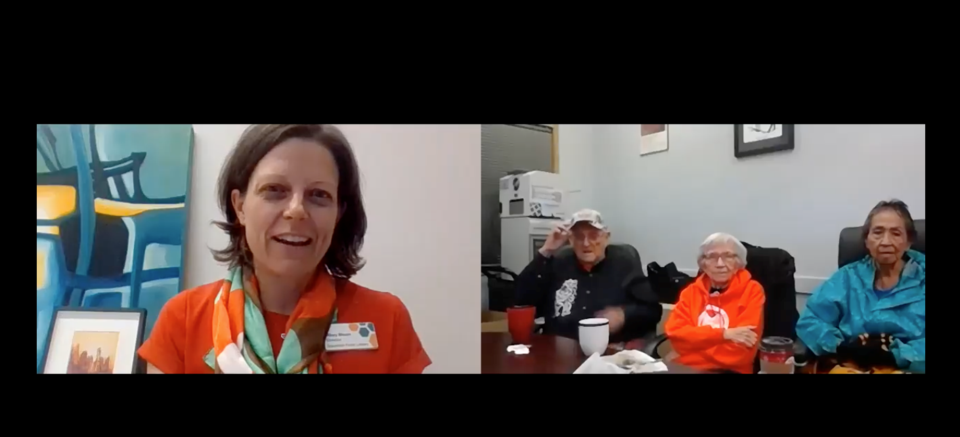

Three 麻豆社国产Elders shared stories of their time in residential schools at a special virtual event on Sept. 29, in honour of the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation Day Sept. 30.

According to the library's executive director, Hilary Bloom, more than 150 logged in online to listen and learn.

In the spirit of continuing that important sharing, The 麻豆社国产 highlights the stories of the evening here.

The elders who shared their stories were Kiyowil (Bob) Baker, who attended , and his sister, Chésha7 (Gwen) Harry, who also attended St. Michael’s; and Humteya (Shirley) Toman, who attended .

The three have been sharing their powerful and often painful stories for about 30 years to help others understand what they and so many others went through.

The trio went to Ottawa when former prime minister on June 11, 2008, on behalf of Canadians for the damage done by Indian Residential Schools.

“It was pretty intense. A lot of tears, anger and frustration,” recalled TlatlaKwot (Christine) Baker, who moderated the library event Wednesday night and also attended in Ottawa.

The three local Elders also attended and shared their stories at the Vancouver (TRC) hearings in 2013.

Though they suffered in the schools, each became vital and contributing members of 麻豆社国产in their adulthood, roles they continue as Elders each time they tell their stories.

They continue to go into local schools and to community events to share their stories.

Kiyowil

After his mother died when he was three, Baker’s grandmother took care of him in Brackendale. She hid him as often as she could so he didn’t have to go to residential school, but he was eventually caught and eventually sent to Alert Bay in the 1940s.

“I didn’t know where I was. I was just lost,” he said of his feelings when he first arrived.

We were not allowed to speak our language.”

Students attended classes half a day and had to work the rest.

He and the other elementary-school-aged boys were abused.

“They were pretty mean. I don’t know why they were so mean. I was getting strapped every morning because I had weak kidneys and I wet myself,” he recalled.

After, he couldn’t pick up a pencil because his hands were so sore from being hit, he recalled. "We didn't know why they were doing that."

He had never seen such cruelty, he said.

One time, in a playroom, a large staff member came in and took off his big belt, and the boys had to run around to avoid him hitting them with the belt. The boys were naked and everybody laughed, Baker said.

“They really made a fool out of us, and there was nothing we could do about it,” he said.

He attended the school for eight or nine years.

The last two years Baker attended the school, he says there was sexual abuse.

"We didn't know anything about that," he said.

“It is not new, but it was ugly —an ugly thing that was happening. We couldn’t tell anyone. They would have laughed and said it was not true,’ he said, noting it wasn't something that was talked about.

The food was "slop" and the boys were hungry so they would get clams on the beach to eat.

When he became one of the older boys, he would try to help the younger ones by, for example, making a fire in a can when they had to work outside, and the younger kids were cold.

One time, he and some other boys ran away and were gone for about a month.

“We hid and they couldn’t find us,” he said.

They stole food to survive, he recalled.

“It was just the way we lived. We had to live that way to survive,” he said, adding he could go on and on with the stories of his time at the school.

“Nobody cared, I figured the whole world didn’t give a damn about us.”

Chésha7

Harry attended the school starting when she was six years old.

She remembers the day she was driven to the school.

“I can see my little brother and sister running after the car,” she said. “That stayed with me.”

She said she didn’t know where they were going and thought she would come back.

When she arrived, the school was huge and there were many girls.

At St. Michael’s, there were 96 girls and 104 boys; students were separated by sex, even from siblings.

“I had no mother, no father, no parents. I had supervisors,” she recalled.

When her brother came, she had to have visiting rights to go see him.

They weren’t usually allowed to go home, even in the summer.

Birthdays were not celebrated and when relatives died, the students were informed but couldn’t leave to grieve with family.

She recalled one time in the summer when the girls were locked in the dorm room, and they took all the beds and stacked them up to keep themselves busy

“We learned how to amuse ourselves,” she said, adding she learned to do somersaults and flips.

That is how they dealt with it, she said.

She caught tuberculosis (TB) at 13 and was sent to hospital.

“It was all Native people in there, and it was also an institution,” she said. “I thought I was dying because of the way they treated me. I was very isolated.”

She was bedridden for about two years.

“They discharged me at the age of 16. I cried, and I didn’t want to go home.... I was a stranger to my own family... This is what happened to me.”

She said truth and reconciliation is about many children, some who were treated more harshly than others.

She never called her father ‘Dad.’ He was a stranger to her; he too had gone to residential school, she said.

“I couldn’t get close. There was no bonding,” she said.

She made sure her own kids were bonded to her, she said.

Humteya

Toman recalled that when she first heard she was being sent to residential school as a child, she was happy because all her cousins were there so she thought it would be a reunion of sorts.

“Not knowing what was behind those closed doors and gates,” she said.

“It was really not what I expected... the abuse too was not something I had ever really seen. I didn’t understand it. I wondered how come these people can do this to us,” she said.

Some nuns were kind, but some were like prison guards and knew what they could get away with.

She said that the verbal abuse was what stuck with her most.

They told the girls that they were ugly and would never be loved, and “would never be more than they were.”

Before she arrived, as the first grandchild, she was cherished, she said, and was welcomed everywhere she went on the reserve.

The nuns said horrible things to her.

“I was going to be a prostitute on the street. I didn’t even know what a prostitute was, but that is what they told me I was going to be,” she said.

They told her teaching her Math and English was a waste of time.

“Pretty soon it started to sink in, ‘Maybe I am not going to be a very good person,” she recalled.

She said even the education that the nuns were trying to teach them was a waste of time.

“You can’t learn when you are being abused,” she said.

She ran away three times.

While away from the school, working odd jobs, she compared the harsh treatment in the schools to the kind of treatment she received from her bosses and coworkers in the community.

“I just decided I am not going to listen to what the nuns are saying and doing,” she said.

She spent the rest of her life searching for and spreading as much love as she could.

“When I found other people who were as kind as my uncles and aunties, I tried to stay with them and learn from them and not listen to the nuns anymore.”

Survival and resilience

TlatlaKwot Baker spoke of the intergenerational trauma caused by the treatment of children in residential schools.

“We have all been affected by this, generation after generation — alcohol and drug abuse, suicide, huge suicide; oppression, depression, abuse of others, cultural identity confusion. So, our culture was taken away completely. Up until the mid-1950s, we were banned from practising our culture across Canada,” she said.

In the 1970s, folks started going back into the longhouses.

“There was like maybe 20 people,” Baker said. “Now, I go into a longhouse and it is full. It is completely full.”

麻豆社国产Nation members are now practising their traditional dances in the longhouse.

“We have people learning our language, from little ones — from babies,” she said.

“We have people in our community now who have graduated, not only just Grade 12 but they are in post-secondary getting their diplomas, degrees, their masters, we have two doctors, I do believe in our Nation. So we are growing strong again. We went from, before contact, we were 10,000 strong, and then we dwindled down to about 250 and now we are up just past 4,100 members. It is growing. It is really growing.”

“I have to say, with the three of these [Elders] and other survivors, they are not the only ones, with survivors of sharing their stories, understanding the importance of their language, their culture, their family — and it is coming back to us.”

She recommended people listen to the stories of other survivors as well because each story is unique.